The Treble Clef

Restrictions of the Tonic-so-fa.

So far we have learnt about how pitch and the tonic-sol-fa provides a medium for understanding music, however there is much more to music than just the tonic-sol-fa. The tonic-sol-fa is used mainly by teachers to teach singers to sing. If we want to fully understand the world of music theory, both written and read, we have to have some understanding of how the notes are displayed. Listen to the following excerpt from “You Raise Me Up.”

You Raise Me Up

Hopefully you heard the change in the overall pitch at about 16 seconds in to the excerpt. (This was a key change – more later). If it wasn’t obvious to you listen again and watch and listen for that change. We can represent changes and embellishments like this writing in the tonic-sol-fa, but as music becomes more complicated the written tonic-sol-fa becomes cumbersome and difficult to both write and read. Fortunately there is a more intuitive system for musicians, and that is the use of sheet music notation. Don’t misunderstand me – there is a very important niche for the fairly simplistic tonic-sol-fa, but that simplicity becomes bloated and restrictive when we start to represent even slightly complex music using the tonic-sol-fa.

The Music Staff.

In our previous tutorial “Pitch and the Tonic-sol-fa” we learnt that notes have pitch and that these pitches can be represented by letters of the alphabet, but how should they be represented in written music? We could of course simply write them as A,B,C etc., but a method has evolved which gives us much more information just by looking at the sheet music (often called a score), so without further ado let’s have a look at an example:

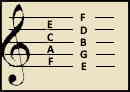

As can be seen, the notes are written on a series of horizontal lines and spaces called a Staff (American) or Stave (UK), By Writing the notes on the staff like this we can see that the notes have a relationship to each other and that this relationship is higher, lower or, if it is the same note, equal. We don’t have to work this out as it is obvious from the position of a note on the Staff. Were we to use A, B, C etc. as pure text, we would have to work this out, but not if we use a music staff. For example, if we examine diagram 1 we can see that there are two note E‘s and looking at the Staff we can immediately see the relationship between the notes. The one near the top of the staff is of a higher pitch than the one at the bottom. Note the names of the notes. The spaces – from the bottom up – spell out the word FACE, so we have a ready acronym to help us remember which notes go in which spaces. The notes on the lines however do not have a ready acronym and so we have to invent one. Many acronyms have been created for this purpose, but the one I first learnt at school is Every Good Boy Deserves Favour, but you can use any one you like. Lets now have a look at the notes on the Staff using this notation.

Notice the symbol to the extreme left of the Staff. This is called the Treble Clef. The word Treble denotes that the pitch of the notes is in the upper, or Treble Staff (there are also other staffs, but we will learn about those later). The Clef (from the French word for key) is an old symbol for G and we can see that this G curls around the second line, or the note G, on the Staff. For this reason the Treble Clef is also known as the G Clef. The two fours indicate the time signature, but that is a subject covered in a later lesson. Also notice that there is a vertical line after the first four notes and another after the next four. These lines are called bar lines and the space between them is called a measure (American) or Bar (UK).

C Major Scale.

We now know that the Staff represents the notes E through E to F and that this represents nine notes and that our simple C Major scale starts and finishes on the note C (See Lesson one). But we have only one C on our Staff, so how can we write the C Major scale in proper music notation? The answer: create notes external to the Staff! Since our starting note is C we can write this below the Staff.

Notice the two notes C and D (do and re) Immediately below the staff. Notice that the note C is on its own line but, this is not a full length line. These short lines, which can be above or below the Staff, are called leger lines. The note C on the first leger line below the staff is actually correctly named C4, but is usually referred to as middle C. There are more leger lines than are shown in the diagram but it is very important that you should memorise all of these notes and which spaces and lines they occupy from the example. It is best to do this now, so take some time out and learn them by rote before continuing. You should be able to look at a note on the staff and recognise it as quickly as you would if you were looking at the algebraic notation (C, D, E etc.).

The C Major Scale.

Below is the C Major scale in standard music notation. Do not worry at the moment if the notation seems strange, everything will become clear in due course. The main points for you to focus on are

- Listen to the notes.

- Look at the note names (above the stave) as they are being played. To be able to sight read or sing music notation you have to recognise every note instinctively, so try to learn and remember them.

- The names of the tonic sol-fa are also displayed below the stave when the scale is playing. It would be worth learning how these relate to the names of the notes in standard music notation.

- Although they are not shown here (this is just the C Major Scale) the three top notes of the staff ‘D’, ‘E’ and ‘F’ should also be remembered (refer to the “Music Staff” paragraph above if you need to) giving you a total of eleven notes to remember at this stage.

Note Values.

When starting to learn music notation many people are confuse by the term “Note Value”. The value of a note is it’s duration in time – not it’s pitch. Each of the notes in the above C Major scale have the same value, i.e. they are all of the same time duration but the all vary in pitch according to their respective places on the staff.

A simple example.

Now that we know the names and pitch of the notes we should be able to play or sing a simple tune. One of the tunes that fits (almost) into the tonic sol-fa (Major scale) is Frere Jacques. We will use the same notes from the C Major scale that we covered in the previous paragraph.

Frere Jacques (Unformatted)

Singing or playing each note for the same value would create a monotony of sound, and so one of the things we can do to make our music more interesting is to vary the value of the notes which make up a tune. The first eight notes of this song vary in pitch but, as we already know, are all the same value Now if this were repeated throughout the song, the song would become very boring and uninteresting. Let’s listen to an excerpt from Frere Jacques where the notes all have the same value (length), I have added the note names below the notes to help forge a relationship between note names and visual notes in the music (don’t worry about the two notes below the middle C in the penultimate and final bars – we shall be looking at them shortly).

How boring was that? As a song it was recognisable, but it was rather boring and lifeless. Yes, the timing was correct, but as a performance it was totally non-inspirational and lacking in colour. Let’s change the value of some of the notes:

Wow! Not the most inspiring tune in the world I agree, but didn’t it come to life? What changed? To help explain this, I have added bar numbers. As you can see from the above music score, vertical lines (bar lines ) group notes into regular chunks, these chunks are called bars or measures. Each bar has a number above which helps us identify a particular moment in the music. The only thing I changed were the note values of some of the notes. The first changes were in bars 3 and 4 where the G notes were double the value of the preceding notes. Continuing on, bars 5 and 6 had four notes each which were half the value of the notes at the beginning. Finally, just like bars 3 and 4, bars 7 and 8 had notes doubled in value. These changes gave the melody a feeling of music and rhythm.

<< Previous Lesson: What is Music?

Next Lesson: Notes and Rests >>